Making young people feel they matter

Antony Mason wrote our new essay on behalf of the Intergenerational Foundation – he describes why making every young person feel they matter is key if communities are to heal intergenerational tension

“This is the only time an adult has asked what we wanted and done it.”

That was one boy’s feedback which Jim Gibson, chair of the Stoke North Big Local, proudly recalls after a trial skateboard park was installed at Monks Neil Park. The expectation of disillusion can clearly start young.

Concern for the wellbeing and futures of the younger generation ranks high in the ambitions of all four of the Big Local areas that I visited to research Local Trust’s new essay ‘Beyond age: Why communities are investing in young people’s futures’: Stoke North, Church Hill, Wick Award and the Coastal Community Challenge.

To varying degrees these communities feel dislocated or forgotten or sidelined by the authorities, with a youth that in turn risks – or already is – feeling alienated.

Youth provision has been particularly hard-hit by local government cuts since the 2008 financial crisis. That’s not just Sure Start and youth clubs, but provision for vulnerable young people such as drug misuse services and youth offending teams. The beauty of the Big Local programme is that communities can identify the problems, even down to an individual basis, and put in the resources to address them. Bottom-up solutions, rather than top-down.

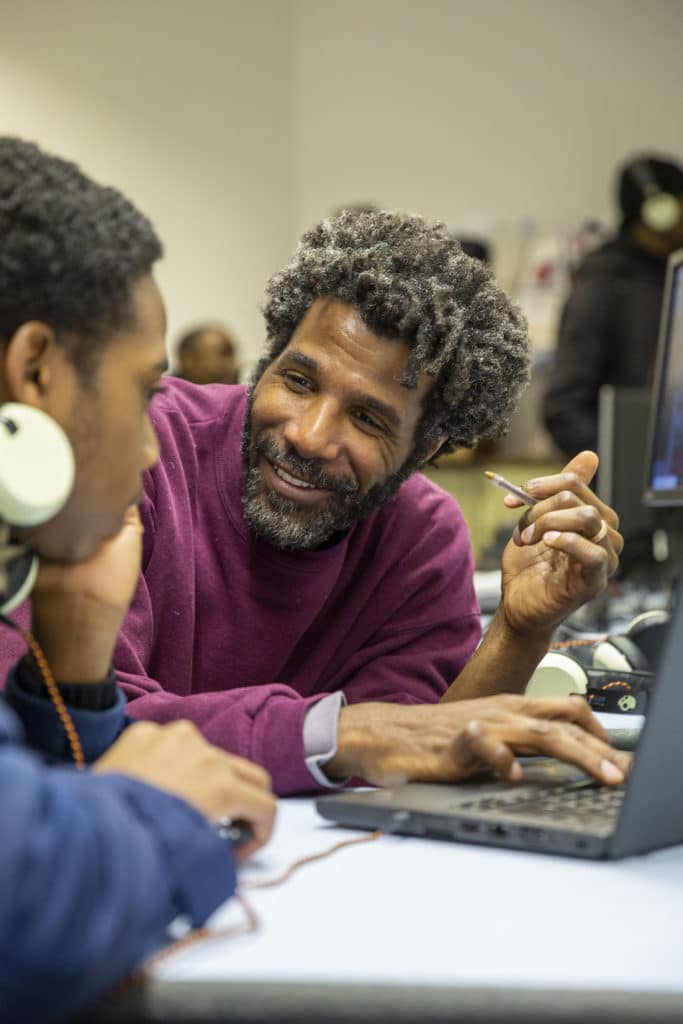

A sense of community is paramount. Luke Billingham, a youth worker at Hackney Quest, a youth club in Hackney Wick which receives funding from the Wick Award, puts it succinctly when talking about the young people excluded from school who are welcomed to the club.

“They matter to us and that’s what weaves you into a community – a feeling that you matter to it and it matters to you.”

I was asked to produce ‘Beyond Age’ as a writer and editor who works for the think tank the Intergenerational Foundation. Since 2011, the Intergenerational Foundation has been looking at the way that Britain seems to have abandoned many aspects of its traditional “intergenerational social contract”: the idea that each generation should pass on to the next generation a world that is at least as good as, if not better than, the one that they themselves inherited.

You can download ‘Beyond age’ and listen to the podcast

In recent months, the growing sense of critical urgency about climate change has focused minds on intergenerational legacy: how the actions and failures of past generations can affect the long-term prospects of future generations.

But this kind of intergenerational tension can also be seen in many other fields of contemporary Britain, where younger generations face the raft of unenviable challenges passed down to them: inadequate and unaffordable housing, set against the windfall property gains that fell into the laps of many of the baby boomers, the prospect of unemployment or careers in low-paid and insecure jobs, the hammer-blow of university tuition fees, diminished welfare support that disproportionately affects working-age families – and a sense that young people are not represented politically.

So how do these issues affect Big Local areas? Every bit as much as the rest of the UK. Both on the Lincolnshirecoast and in Hackney Wick, for instance, the young are forced move away from their parents for training and work or because of housing costs, fracturing the family networks of mutual support traditionally offered by generations living in proximity.

“Young people are not heard,” says Kelsey, a 17-year-old A-level student in Hackney.

“Adults speak on behalf of children as if they know what we are thinking. We’ve lost hope for votes at 16. We’re set up with the future that is set up for us – we don’t have an opportunity to change it. Politics is forever breaking trust with young people.”

But one way of starting to mend these fractures between generations is by building, or rebuilding, a sense of community. And that is what the Big Local programme can do – and they are making headway in the four Big Local areas that feature in this essay. Money isn’t everything, of course, but it certainly helps. Holiday play schemes, youth clubs, school mentoring services, help with preparing for the workplace, intergenerational activities in sport or gardening or crafts or one-off day trips to local attractions – all help to build this sense of inclusiveness, the feeling that you matter.

There are big lessons here for policy-makers and funders. Could they be rolled out on a national scale?