Social infrastructure refers to the framework of institutions and physical spaces that support shared civic life. Places like community centres, pubs and parks provide space for people to meet, engage, and build relationships and trust that underpin any successful community.

Other elements are less visible and tangible – the networks of formal and informal groups, organisations, partnerships and initiatives that both benefit from and sustain the physical and social fabric of a place.

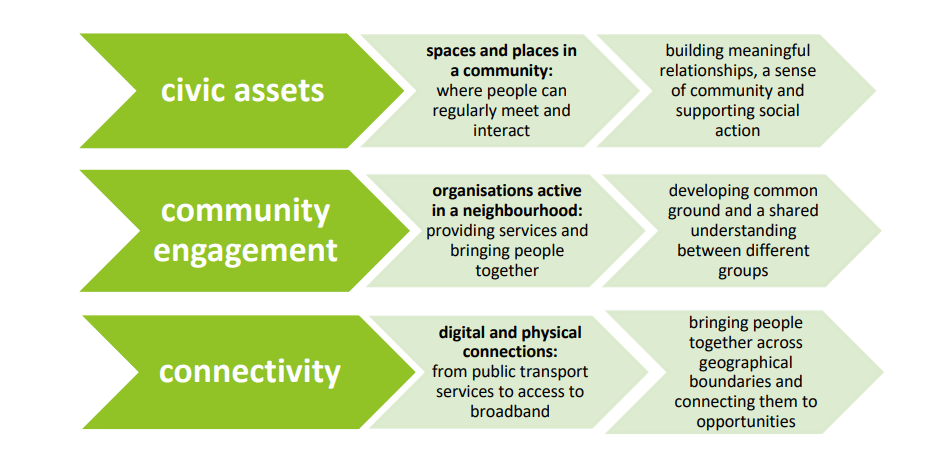

While definitions of social infrastructure vary, Local Trust breaks down this resource into three core elements, including:

- the physical infrastructure within the local area that supports the formation and development of social networks and relationships

- the community-based groups and neighbourhood associations that turn those community places and spaces into thriving hubs of civic life and activity, and

- physical and digital connections – from public transport to internet access – that are crucial for bringing people together and linking them to social and economic opportunities

A breakdown of the elements of social infrastructure used by Local Trust:

Why is social infrastructure important?

A growing body of evidence has shown the vital role of social infrastructure in building safer, healthier, more prosperous and resilient communities.

There has also been increasing recognition of the role that social infrastructure plays in improving socioeconomic outcomes in deprived areas, and as a foundation for economic growth more generally.

Local Trust’s experience of delivering the Big Local programme has underlined the importance of social infrastructure, to enable deprived communities to take action themselves and improve their areas.

- Social infrastructure builds trust and social capital

Having spaces to meet, an engaged community, and accessible connectivity are all critical in forming, supporting and boosting the levels of social capital in a local area.

Social capital is not just the glue or the ties that bind us together by fostering trust and reciprocity: it’s essential for wider social and economic health and wellbeing – something that has become particularly important to communities seeking to respond to challenging social and economic circumstances.

- Social infrastructure and social capital strengthen community resilience

Strong connections between residents and organisations allow a community to work together to navigate crises, providing specific assistance during times of trouble.

As individuals form stronger bonds, they share more information about their lives, developing an understanding of each other’s needs and skills, making communities better able – and willing – to solve problems collectively.

- Social infrastructure improves economic outcomes

Social infrastructure helps build levels of social capital across communities and the skills and networks needed to access the labour market.

Civic assets, such as community hubs, bring opportunities for individuals to develop the skills and networks needed to progress in employment opportunities. Furthermore, a well-connected neighbourhood, both physically and digitally, is needed to access many paths of employment.

Low levels of social capital can help to explain why it is difficult for individuals who live in the most deprived neighbourhoods to find the type of employment opportunities that can help them to exit poverty.

‘Left behind’ neighbourhoods and social infrastructure

Local Trust commissioned Oxford Consultants for Social Inclusion (OCSI) to develop a Community Needs Index (CNI) based on our experience of delivering the Big Local programme in deprived areas.

The CNI identifies and tracks where social infrastructure has been most severely eroded. Overlaying the CNI with the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) makes it possible to identify those neighbourhoods which are both severely deprived and have the least social infrastructure in the country.

From this, 225 neighbourhoods have been identified as ‘left behind’: the communities identified as the 10 per cent most deprived on both indices. These places suffer from the double disadvantage of high levels of deprivation and a lack of social infrastructure.

These areas experience notably poor outcomes – not only compared to affluent areas, but also compared to places that are equally deprived but where a base layer of social infrastructure has nonetheless been retained.

Read more

- Report: APPG for ‘Left behind’ neighbourhoods session report on social capital and social infrastructure and why it matters

- Blog: Keeping social infrastructure on the agenda

- Policy spotlight: How social infrastructure improves outcomes

- Blog: Three lessons on revitalising communities and social infrastructure

Photos (from top)

Crowd at Winterton Big Local community unveiling of sculpture of Professor Wallace Sargent. Photo: Local Trust/ Roger v Moody

Windmill Hill Community Centre opening event. Photo: Local Trust/Danyelle Rolla

Visiting the MPower Kernow workshop with Par Bay Big Local. The project provides transferrable STEM skills for those from underprivileged backgrounds. Photo: Local Trust/Charlotte Sams