Elaine Lovell is fighting a national campaign against pay-to-use cash machines in poorer areas – limited access to free ATMs in Hill Top and Caldwell is costing residents here more than they may know

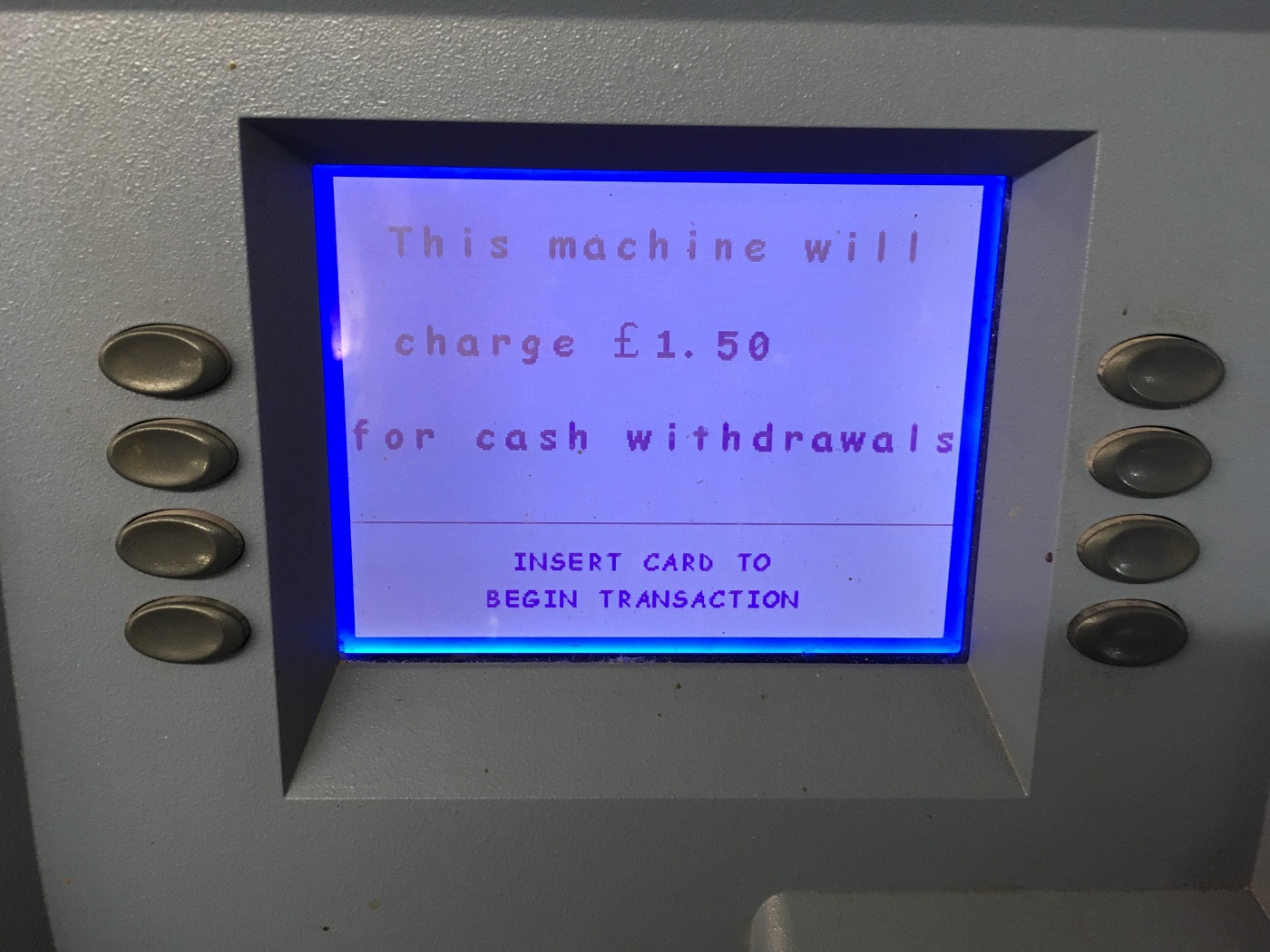

It’s a chilly day in early spring when Elaine Lovell walks me towards her local corner shop in the Hill Top and Caldwell area of Nuneaton. “That’s where my nearest ATM is, and it costs £1.50 every time I take money out,” she says. “This is a multiply deprived area and it’s costing people here more than they probably know just to get hold of their own cash.”

Lovell is a member of Hill Top and Caldwell Big Local, and over the past two years has become a committed campaigner against pay-to-use cash machines in poor areas.

There are two ATMs that charge in this Big Local area: this one in Caldwell Stores, and another up the hill. There are two other free-to-use machines but they’re further away: one is over two main roads, and the other – just within the kilometre that regulations require between free-to-use ATMs – is not, Lovell says, accessible to residents without transport. “Lots of people here, they struggle to walk, or they’re old or they don’t have a car,” she observes. “They can’t just nip out.”

Lovell makes a point of saying that she doesn’t begrudge the shopkeeper at Caldwell Stores the money she makes from having the ATM on her premises: she says she’ll be “eternally grateful” to her for taking over the shop when it was empty. But as she also observes, “I bet she doesn’t get anything like £1.50 per withdrawal! Most of it’s going to the machine company.”

We walk on over the canal and up the hill to Hilltop Stores, which has the second pay-per-withdrawal ATM on the estate.

“There’s about a third of people on benefits in this area”, Elaine says, “so it’s taxpayers’ money and it’s going straight to the people who want to make a profit.”

That profit is costing the people of Hill Top and Caldwell dear. “There’s this one girl,” Lovell says, “she’s got five kids. Her youngest has a job but he’s not got a car, so he’s up the shop to get his bus fare a couple of times week, and that’s £1.50 every time he gets out a tenner. And then his mum toddles off to get her money, twice a week. That’s £6 they’ve had off that family. And they’re a low-income family.”

But Lovell is not relying on anecdotes. Encouraged to build an evidence base for her campaign by her Big Local colleagues, she recently made a compelling calculation. Over the course of a year, she worked out, a family living on the estate which makes one withdrawal per week from one of these cash machines will lose £78.

“Scaled up to 100 families, the annual financial loss to the community would stand at £7,800.”

But imagine two parents and a couple of teenagers, making a total of four withdrawals a week: over a year, 100 such families will have handed over £31,200 simply to access their own cash. In an area of multiple deprivation, a loss of income on this scale is significant. Multiply it up across poor areas of the country and it becomes huge. This, Lovell points out, is money that could be circulating in the community, rather than being siphoned off to ATM-providers who have no connection to the area.

Over 97% of ATM withdrawals made in the UK are currently free. But according to a Barrow Cadbury report, 16% of people live more than the mandated one kilometre away from a hole-in-the-wall that won’t demand they cough up. And ATM providers are warning that free access to cash may soon be a thing of the past.

In response to this threat Lovell is determined to alert policy makers to the unfairness she perceives is being visited upon fellow residents in this Big Local area: as well as campaigning locally, she recently submitted evidence to the Treasury Select Committee in their hearing on access to ATMs.

“The poorest people are being extorted: I think I’ve been more aware of this sort of thing since learning about financial abuse in my care work,” reflects Lovell. She understands why ATM providers need to ensure their machines are financially viable by charging a fee. What she “struggles to understand” however, is how the nationwide Link system – the interbank network of cash machines – says that its financial inclusion programme, designed to ensure areas like her own have access to free ATMs, cannot help where she lives.

Lovell takes me to meet Big Local chair Ann Cox and vice-chair Eileen Young. Counteracting poverty is a priority area of work for the partnership, Cox explains. “I’m 100% behind Elaine,” she says. “Lots of young girls here are on a low income and family tax credit, and they don’t want to take all their money out at once.”

“Or they’ve got a nasty partner who’ll rob their purse,” says Young.

Cox nods. “Or their kids will.”

There is controversy in the world of ATM providers, after Link recently decided to lower the amount it pays per withdrawal. While the ensuing outcry resulted in the scale of the cut being somewhat mitigated – and in some remote areas, Link will now actually pay more – in other places. Lovell says, the reduction in payment means certain machines are simply being removed, while others are switched to “pay-to-use.”

“Of course, more of society is going cashless. But for people on extremely low incomes who need to budget day by day, this may never be a realistic option.”

So what does Lovell think should be done?

She has lots of recommendations. Among them, she says that government needs to intervene so that all residents can have safe and easy access to a free cash machine. Although not all ATMs are part of the Link network, she believes that Link should volunteer to pay subsidies and offer other support to incentivise shop owners in deprived areas to switch to free ATMs: this would compensate for their lost earnings from existing “pay-to-use” machines.

“My shopkeeper runs her business in a place where people don’t have a lot of money to buy stuff so I’m sure she needs that income,” she points out.

Lovell knows that an issue she has identified locally is affecting people nationally: she is determined to persuade those in charge of how we access our cash that the poorest must not be seen as soft targets for companies in search of high profits.

“People are getting rich off the poor,” she says. “And I don’t think it should be allowed.”

This feature was written by Louise Tickle, our journalist-at-large. If your Big Local area has a story you’d like to share with Louise, you can email her.