‘Left behind’ communities need more than regional investment to thrive

Senior policy officer Rayhan Haque reflects on the recent call on government to ensure ‘levelling up’ is achieved in northern constituencies and considers what more needs be done.

A letter published last week set political pulses racing. It was from the Northern Research Group (NRG) – a new grouping within the Conservative Party led by former northern powerhouse minister, Jake Berry MP. He has described it as “a trade union for northern MPs”.

In truth, it’s more akin to an internal faction representing the interests of northern Conservative MPs in former ‘Red Wall’ seats which helped secure the Prime Minister his hefty majority government in December 2019. And with 55 MPs in their ranks, they naturally attracted the spotlight.

Key points from the letter

So, what did they say in their letter to the Prime Minister? Three key messages stood out.

First, to provide a “clear roadmap” out of lockdown restrictions, which are “disproportionately” affecting the North. They warned that COVID-19 has “exposed in sharp relief the deep structural and systemic disadvantage faced by our communities”.

Second, they expressed worries that “the cost of COVID-19 could be paid for by the downgrading of the levelling-up agenda, and northern constituencies like ours will be left behind”. It’s worth noting that Number 10 did respond by reaffirming they “are absolutely committed to levelling up across the country and building back better after coronavirus.”

And finally, they lobbied the government to double down on their promise to invest in the North’s infrastructure, like rail links and ultrafast broadband. The letter was right to highlight the country’s deep regional inequalities, which in terms of productivity, income, unemployment, health and politics, are consistently more severe than any comparable country in the OECD.

Pockets of deprivation often exist next to prosperous areas, leaving communities socioeconomically disadvantaged.”

However, the letter seemed to overlook the fact that spatial inequality across the UK runs deeper and is more complex than the ‘North-South’ divide; regional inequalities intersect with disparities in opportunity and outcomes between local government areas and, more specifically, between neighbourhoods.

Inequalities at the neighbourhood level

Local Trust has mapped and identified 225 areas (using ward level data) in England facing the highest levels of economic disadvantage in addition to a lack of social infrastructure and civic assets. These ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods are concentrated in post-industrial areas in northern England. But they are also found in coastal areas in southern England in addition to post-war social housing estates on the peripheries of cities and towns.

This demonstrates that pockets of economic disadvantage sometimes exist next to more prosperous areas, leaving some communities with acute levels of socioeconomic deprivation and very limited social infrastructure; feeding a sense they are not reaping the benefits of resources and investment targeted at larger economic areas or regions.

Places to meet was cited as the main resource that ‘left behind’ felt they were missing out on.”

The NRG letter also failed to mention the importance of investing in social infrastructure and social capital, which is fundamental to levelling up and ensuring that no community ever feels ‘left behind’.

View from the streets

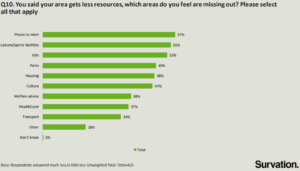

Local Trust recently commissioned Survation to poll people in these ‘left behind’ areas. It found that people living in those neighbourhoods feel they are missing out on places to meet and community facilities when compared to other places. Of those saying their community was getting less, places to meet was cited most often as the biggest area where ‘left behind’ communities were not getting their fair share (57%).

This was closely followed by community facilities such as leisure and sports facilities (55%). This highlights the importance that residents in ‘left behind’ communities place on local social infrastructure – places to meet and other community facilities which bring people together. They were both seen as more important than investment in job opportunities and tackling unemployment – the third highest priority at 53%.

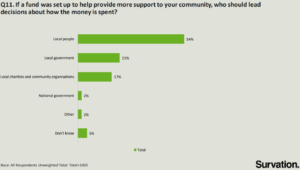

Survation’s research also underscores the importance of community power, with 63% agreeing that when local people do get involved in their community, they really can change the way that their area is run.

What next?

The NRG letter has helped to amplify the importance of levelling up the most ‘left behind’ areas. It cannot though, be viewed simply as a ‘North-South’ issue. Instead, it must be considered through the lens of communities, at the neighbourhood level, and anchored around major investment in social infrastructure and nurturing of powerful communities. Anything less, and people in those ‘left behind’ areas seeking real improvements, will remain disappointed.