A new house and home for everyone on the Brookside estate

How Brookside Big Local has embraced people struggling to recover from drug and alcohol addiction, and adapted its partnership meetings to welcome everyone

The Brookside estate in Telford is a maze of narrow lanes bordered by red brick housing and high wooden fences. Walking through the estate which is home to nearly 5,000 people, it’s hard to tell where you’re going: Sam Pitch, the Big Local co-ordinator, picks her way unerringly around corners and along winding paths till she stops in front of a semi-detached house in a cul-de-sac.

“We can’t go into the one we’re buying yet,” she explains. “But it’ll be run in the same way this one is.”

“This one” is a house for four men recovering from drug and alcohol addiction. Run by the charity A Better Tomorrow, which provides 24-hour support to both men and women who have experienced substance misuse, self-harm or eating disorders, the home is a haven in the middle of a community where residents, Pitch says, have tended to be sympathetic to those who struggle with destructive behaviours.

“Plenty of people in Brookside will have had those issues in their own lives or come across it with friends and family,” she says.

To help the charity address demand – “we’ve got a waiting list as long as my arm” says founding director Paul Gallagher, a former pub landlord who is himself a recovered alcoholic – Brookside Big Local has just opted to buy another house on the estate. You get a lot of house for your money in this area: the five-bedroomed property which cost £90,000 will be leased for 10 years and then gifted to the charity to enable it to continue its work.

But Pitch doesn’t yet have the keys to the new purchase, so Gallagher opens the door to this property. It’s spotlessly clean and so tidy that despite the comfortable second-hand sofas, armchairs and a coffee table in the living room, it feels almost bare inside. “People come in and they’re chaotic,” Gallagher says. “We give them constant support, help them with volunteering and different activities, get them onto training courses at college too. Some of the guys take 12 months just to find themselves again.”

The two-year programme, he says, means that by the time clients leave, “they have structured lives. Some of them have got their families back.”

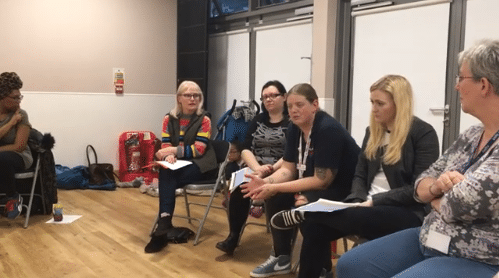

That evening, at Brookside Central Community Centre, the decision to buy the house must be formally reviewed by the partnership board and any residents who choose to attend. Food is put out in the big, airy meeting room, and rapidly demolished: it’s not only 16 adults who have turned up, but seven kids ranging in age from a tiny boy who is just about toddling to children at the upper end of primary.

“It didn’t used to be like this – it used to be a boardroom table and for me that wasn’t comfortable,” says Brookside BL chair Shana Roberts. “It felt very formal with papers and minutes, and that’s not what all this is about. It’s about people who live here trying things out.”

“So, what have you learned through buying this house?” asks Helen Fairweather, Brookside BL’s local rep, after Roberts has opened the meeting.

“That it’s really, really hard work,” says Pitch, clearly relieved that completion is just around the corner. “We had to move fast and that made it intense.”

One resident expresses some disquiet. “I think the council is absolutely useless, but the problem is that you’re doing what they should be doing. Can’t you ask them for a grant?”

Roberts explains that Big Local is not permitted to use its money for statutory services. Clearly however, with cuts, there may be services such as drug and alcohol rehabilitation that councils could once have paid for on a discretionary basis that are no longer commissioned.

Children mill around throughout the meeting. Surprisingly, this is not particularly disruptive, as there is an expectation that noise – and indeed children themselves – are acceptable. All agenda items are dealt with in less than 90 minutes: a local welcome pack for new residents is mooted and approved; two local mothers introduce their stay-and-play idea, which invites health and wellbeing professionals to talk to local parents and grandparents at informal sessions; a woman who had experienced domestic abuse and asked BL to fund her to become a Freedom Programme trainer is now getting accredited to go into schools and talk to young people about healthy relationships.

“The dynamic is warm, welcoming and slightly chaotic – but it seems to work.”

“Think of the people who we’d be missing hearing from if the kids couldn’t be here,” says Roberts. “We’ve just found a parent with grant-writing experience who wouldn’t be able to come so easily without bringing her kids.” “I’m just glad to see this room full,” laughs BL vice-chair Clare Lloyd. “I remember when there were only six of us.”

This feature was written by Louise Tickle, our journalist-at-large. You can contact Louise directly if your Big Local has a story you want to share.